Author: Sajjad Sheikhi

U.S. inflation is only available through September!

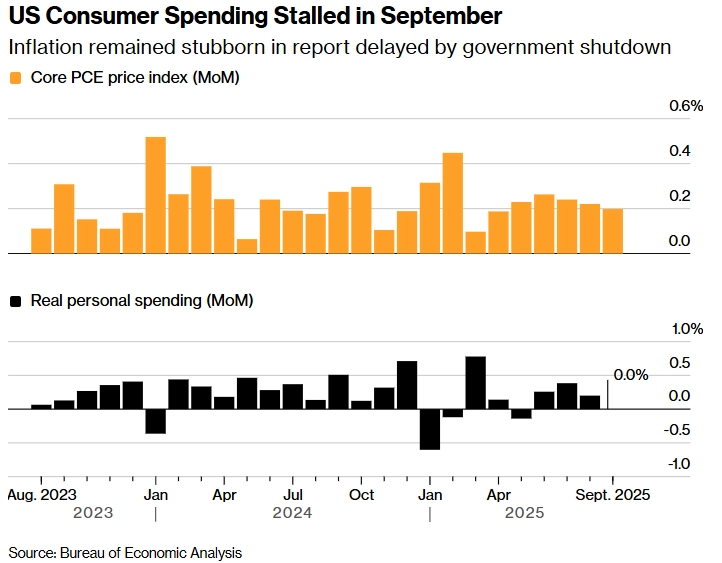

Due to the U.S. government shutdown, inflation data for October and November is unavailable. Interestingly, according to the White House, October inflation will not be released for the first time in history. Nevertheless, the inflation trend through September will not prevent an interest rate cut at this meeting.

According to reports:

• Core PCE inflation for September was 0.2 percent month over month and came in as expected.

• If this annualized trend continues, the yearly inflation rate will be around 2.4 percent, which is close to the Federal Reserve’s target.

• Inflation growth in services has also declined, consistent with the November PMI report, which shows falling prices in the services sector.

As a result, the 2.8 percent headline inflation still above the target creates limited room for rate cuts in 2026. Hawkish members are focused on this point, while dovish members are more concerned with labor market weakness, slowing wage growth, and declining real consumption.

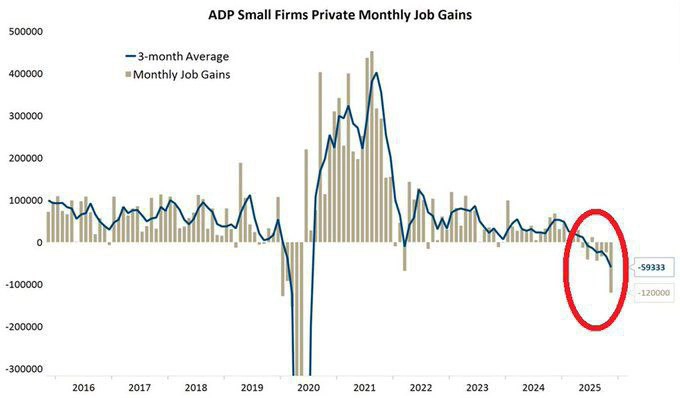

The class divides in the economy

The recent growth of the U.S. economy is described as K-shaped, meaning that economic growth is being driven only in certain industries and groups while other sectors are contracting. Examples of this divergence include:

• The divergence between the manufacturing and services sectors in PMI reports

• Consumption being driven primarily by high income households (according to the Federal Reserve’s Beige Book)

This divide stems from previous fiscal policies including tax cuts and stock market growth which, despite high interest rates, have primarily benefited the wealthy, while the middle class is facing a weakening labor market.

Based on ADP data:

• Small businesses have reported job losses in 6 out of the past 7 months.

• Net job creation over these 7 months has been negative 264,000.

Additionally, BLS reports show that the unemployment rate has risen and wage growth has slowed.

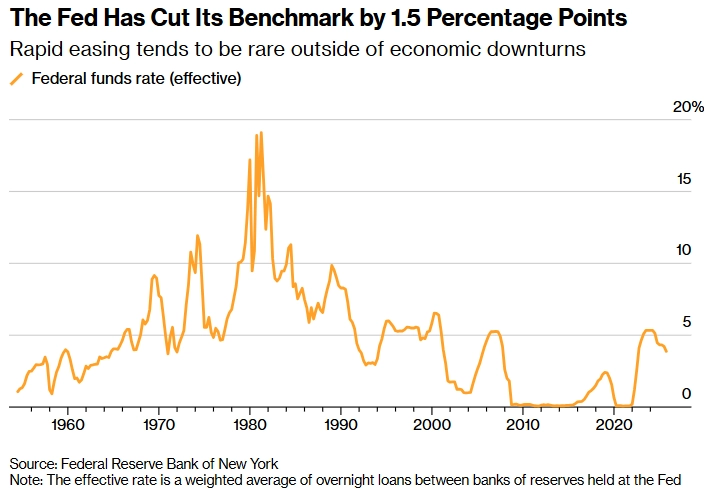

Similarity of the rate cut cycle to the 1960s

The Federal Reserve has reduced interest rates from their peak at the fastest pace since the 1980s, and Deutsche Bank warns that accelerating rate cuts while the economy is not in recession could intensify inflationary pressures. Fiscal policies have become highly expansionary, the stock market is swinging near record highs, and economic growth remains acceptable.

Deutsche Bank warns that this cycle resembles the rate cut episodes of the 1960s in the United States and the 1980s in Japan, during which inflation surged sharply afterward and central banks were forced to return to a tightening cycle. In the 1960s, the Federal Reserve cut interest rates by 200 basis points. At the same time, fiscal policy was eased, and inflation rose dramatically to 6 percent by the late decade. A similar situation occurred in Japan in the 1980s, leading to a massive asset bubble that left devastating consequences for the economy.

Why might Deutsche Bank’s claim be incorrect?

If we look only at monetary policy, the situation shows some similarities; however, there are other factors that differentiate this period from the 1960s. In the 1960s, fiscal easing was driven largely by the costs of the Vietnam War, which increased government spending and the budget deficit. As a result, money creation led to inflation. But in 2025, there is currently no geopolitical risk of that scale, and more importantly, there has been significant progress in artificial intelligence, which is boosting productivity. We expect productivity gains to partially offset inflationary pressures.

On the other hand, in the short term, we are seeing labor market weakness, which has dampened demand. This also softens inflation.

Therefore, based on these assumptions, interest rates can be reduced a bit more without likely triggering intensified inflationary pressure. But the key point is that part of the labor market weakness stems from AI replacing workers. This issue cannot be solved by lowering interest rates; that is, beyond a certain point, rate cuts cannot help the labor market.

In the long term view, artificial intelligence may slightly increase the neutral interest rate because it strengthens economic growth. However, the full impact of AI on the economy is still unclear, as it is not yet known exactly how the labor market and demand will be shaped. This factor will have a significant effect on inflation and the neutral interest rate.

To what extent can AI contain inflation?

Kevin Hassett (the likely Federal Reserve Chair after Powell) has stated that we can reduce interest rates substantially because productivity gains from AI will keep inflation under control. Again, there is some exaggeration here. AI can help contain inflation, but not when interest rates are cut excessively. These factors must move in balance.

Dot plot and the Fed’s new projections

In this meeting, the Fed’s dot plot and updated projections will be released. In the September dot plot, as shown in the chart below, Federal Reserve members on average anticipated one rate cut in 2026 and one in 2027.

We expect the same amount of reduction for 2026, but overall, the dots will likely shift upward (more hawkish). The estimate of the neutral interest rate in the SEP may also come in above 3 percent.

Summary

The upcoming Federal Reserve meeting includes the release of the dot plot, updated economic projections, and Powell’s speech.

The market has priced in two rate cuts, but Federal Reserve members expect only one cut in 2026.

Close attention to the dot plot, the SEP (especially the neutral rate), and Powell’s remarks is crucial for analyzing the interest rate outlook for next year.

This decisive meeting will provide market participants with clear signals about monetary policy and the trajectory of interest rates in 2026.